Obscure yet potent: Mobile phone surveillance tool in operation nationwide

CellHawk is a tool utilized by law enforcement to process and visualize vast amounts of data obtained from cellular towers and providers. Its advanced capabilities enable law enforcement to more effectively utilize the information collected.

For years, Hawk Analytics and its powerful mobile phone surveillance tool, CellHawk, have operated largely unnoticed by the public. Law enforcement agencies, private investigators, and the FBI across the US have embraced the tool, allowing them to convert information collected by cellular providers into maps that reveal individuals’ locations, movements, and relationships. However, police records obtained by The Intercept reveal that the tool has been operating in obscurity with little oversight, raising concerns about the extent of its use and potential abuse.

CellHawk’s manufacturer claims that it can process an entire year’s worth of cellphone records in just 20 minutes, revolutionizing the investigative process that once required painstaking work and hand-drawn paper plots. The web-based product can handle call detail records (CDRs), tracking cellular contacts between devices, and cellular location records that monitor phones’ connections to various towers as their owners move around.

The data that CellHawk collects can also include “tower dumps,” which list all phones that connected to a specific tower, creating a form of dragnet surveillance. In one example, the FBI obtained over 150,000 phone numbers from a single tower dump to collect evidence against a bank robbery suspect in 2010, according to a report from NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice.

Law enforcement agencies use CellHawk to process large datasets they regularly receive from cellular service providers such as AT&T and Verizon. These datasets typically come in the form of wide-ranging spreadsheets, and in many cases, without a warrant. Unlike the more well-known stingray technology, which uses a mobile device to impersonate carriers’ towers to spy on cellular devices, tricking phones into connecting and then intercepting communications, CellHawk does not require such subterfuge or the need for police to position themselves near individuals of interest. Instead, CellHawk helps law enforcement agencies take advantage of information that has already been collected by private telecommunications providers and other third-party sources.

CellHawk’s surveillance capabilities go beyond analyzing metadata from cellphone towers. Hawk Analytics claims it can churn out incredibly revealing intelligence from large datasets like ride-hailing records and GPS — information commonly generated by the average American. According to the company’s website, CellHawk uses GPS records in its “unique animation analysis tool,” which, according to company promotional materials, plots a target’s calls and locations over time. “Watch data come to life as it moves around town or the entire county,” the site states.

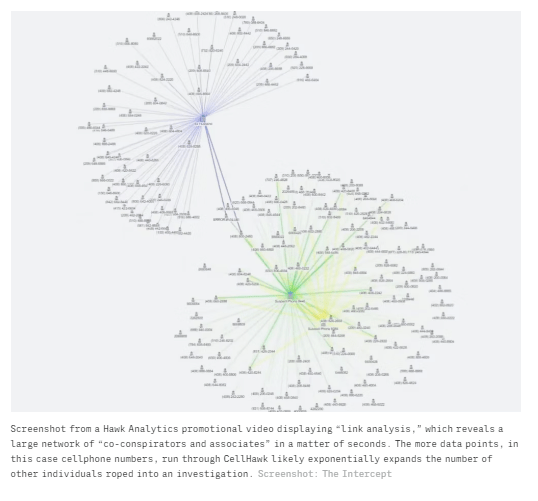

The tool can also help map interpersonal connections, with an ability to animate more than 20 phones at once and “see how they move relative to each other,” according to a promotional brochure.

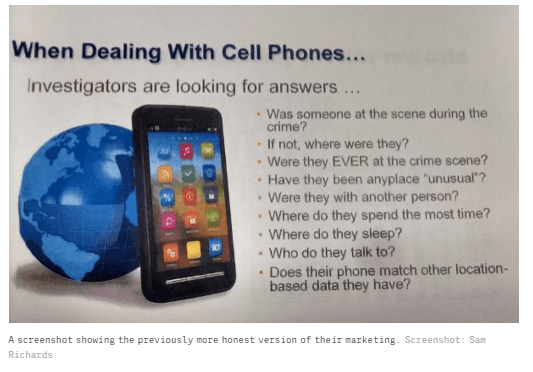

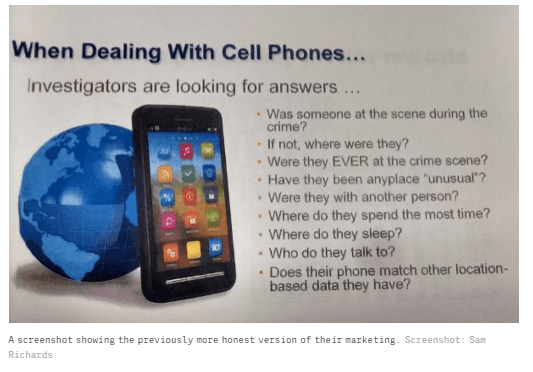

Hawk Analytics has marketed CellHawk as a tool for automated and continuous surveillance, rather than just a tool for processing occasional spreadsheets received from cellular companies. The company’s website promotes the tool’s ability to send email and text alerts to “surveillance teams” when a target moves or enters or exits a specific location or Geozone (e.g. the entire county border). According to Hawk Analytics, this feature can help investigators “view plots and maps of the cell towers used most frequently at the beginning and end of each day.”

However, in brochures provided to potential clients, the company’s language is much more explicit. Hawk Analytics claims that CellHawk can help law enforcement “find out where your suspect sleeps at night,” demonstrating the tool’s potential to be used for invasive and continuous surveillance.

Minnesota’s Loose Regulations and Data Sharing Practices

The sheriff’s office in Hennepin County, Minnesota, which includes Minneapolis, certainly seemed impressed after it started using the software in early 2015. One criminal intelligence analyst lauded CellHawk’s ease of use in a February 2016 email comparing the subscription software to a competing tool. “CellHawk is pretty new and a lot cheaper! The great thing about cellhawk is that it is ‘hands off’ by the user, as the software does everything for you. It is drag and drop. The software can download calls from all major phone companies. The biggest selling point is of course the mapping. it also has animation, which is cool!”

Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office uses CellHawk as part of an effort to share intelligence through a Minnesota fusion center known as the Metro Regional Information Center, which brings together the FBI and eight counties serving up to 4 million people, according to the St. Cloud Times. In February 2018, the latest year for which The Intercept obtained HCSO invoices, the sheriff’s office renewed its annual subscription, providing the capability to store 250,000 CDRs.

A spokesperson for the sheriff’s office, Andrew Skoogman, said the office used certain CellHawk features infrequently. For example, it is “extremely rare” for HCSO to analyze tower dumps, he said, and “fairly rare” for it to use CellHawk’s automated location alerting service, which is used “based in the analytical needs of the investigator.”

The telecommunications data at the heart of CellHawk is shared extensively by providers. For example, Verizon in 2019 received more than 260,000 subpoenas, orders, warrants, and emergency requests from various U.S. law enforcement entities, including more than 24,000 for location information. But the legal requirements for obtaining that information are sometimes unclear. The American Civil Liberties Union in 2014 called the legal standards related to tower dumps “extremely murky.” A 2018 Brennan Center report stated that the courts were “split” on the handling of such dumps, with some lower courts allowing access to the data using a court order, which under the Stored Communications Act is obtained using a lower evidentiary standard than a warrant, requiring only “reasonable grounds to believe” the records are relevant to an ongoing investigation. Location records particular to a given subscriber, meanwhile, can be obtained with just a court order — unless they span seven days or more, in which case police need to get a full warrant, according to a 2018 Supreme Court ruling. Courts have also been divided on whether police need a court order or warrant to obtain “real-time” cellular location data.

Hennepin County defined its own legal standards to rely upon in deploying technology like CellHawk. These were articulated in a sheriff’s office policy document dated August 2015 — months after CellHawk was already in use. The document, titled “Criminal Information Sharing and Analysis,” was released following a data request that was initiated in 2018 and fulfilled several years later following the election of a new sheriff. It stated that the office needed “[r]easonable suspicion,” which was deemed “present when sufficient facts are established to give … a basis to believe that there is, or has been, a reasonable possibility that an individual or organization is involved in a definable criminal activity or enterprise.”

The policy does not say that investigators must receive approval from a judge to retain information. Skoogman did not respond to The Intercept’s question about what legal standard is applied to the collection of CDRs.

Chad Marlow, senior advocacy and policy counsel for the ACLU, when asked to review Hennepin County’s CellHawk policy, said the CellHawk technology was “not inherently problematic” but that the county set a low standard for how it handles the collection of CellHawk data. Requiring “reasonable suspicion” is a typical threshold for traffic stops, not for intrusive searches, which require probable cause. CellHawk’s capabilities — combing through data from calls, texts, ride-hailing applications, etc. — are patently more intrusive than a traffic stop. Beyond that, Marlow said, the county’s “definition of reasonable suspicion is bizarrely convoluted” and should require that investigators “have to have a reasonable basis for a crime being committed not MAY BE being committed.”

Hennepin County’s policy continued:

Criminal intelligence information shall be retained for up to five years from the date of collection of use, whichever is later. After that time, this information shall be deleted unless new information revalidates ongoing criminal activities of that individual and/or organization. When updated criminal intelligence information is added into the file on a suspect individual or organization, such entries revalidate the reasonable suspicion and reset the five year standard for retention of that file.

The policy empowers HCSO investigators to scoop up this data and retain it for five years based on a fairly low legal standard.

Although the policy states that the sheriff cannot keep information solely based on support for “unpopular causes” or personal characteristics such as race, gender, age, or ethnic background, along with First Amendment protected activities, data collected during a protest could still be used by law enforcement in the event of a crime. With low standards and a powerful surveillance tool like CellHawk, it wouldn’t be difficult for law enforcement to map out the entire social network of a protest movement. This could have serious implications for privacy and civil liberties.

During a protest in Minneapolis, 11 individuals were arrested and held on probable cause for riot, property damage, and unlawful assembly. If their information was run through CellHawk by criminal intelligence investigators, the police could have access to a map of their associations based on their calls, texts, and other records. This could potentially include thousands of activists who were not involved in the crimes these individuals are accused of committing. Hawk Analytics promotes social network analysis as a primary feature of CellHawk.

When asked if the use of CellHawk undermined the presumption of innocence, essentially reversing the investigative process so that evidence comes first and suspicion of a specific crime after, Skoogman replied that innocent people had nothing to fear. He explained that individuals come under suspicion based on information developed by investigators and that evidence collected from the analysis of cell phone records may actually clear a suspect of wrongdoing. Skoogman emphasized that this is the investigative process and data analysis is used to determine whether the data supports continued focus on an individual as a suspect or possibly rules them out entirely.

CellHawk: Widely Used and Marketed Across the United States

Hawk Analytics CEO Mike Melson, whose bio on the company website describes him as a former NASA engineer, offers free trials to law enforcement organizations to which he hopes to sell his product. Additionally, Melson has worked as an expert witness, ready to testify on behalf of prosecutors. His testimony sometimes appears in local news outlets without mention of the fact that he is the CEO of the company that could stand to financially benefit, albeit indirectly, from a conviction. Hawk Analytics failed to comment on the record after multiple attempts were made over the phone and by email.

During the trial of Tammy Moorer, who was convicted of the murder of Heather Elvis, Dave Melson appeared as an expert witness on cell phone data analysis. It was not mentioned that Melson had a hand in creating software that played a role in the investigation. According to WBTW News 13, Melson’s testimony was crucial in connecting the dots in the case.

Hawk Analytics was also reimbursed for their expert services in a murder case in Northern Virginia. For analyzing cellular data and providing two days of expert testimony, the company was paid $8,175. While this amount may not be substantial, it adds to the company’s revenue streams from various parts of the criminal justice system, including the sale of CellHawk subscriptions.

CellHawk is not the only technology that investigators in the Twin Cities use to process intelligence about suspects and others. Hennepin County and their law enforcement partners use automated license plate readers; stingrays and competing, similar devices; aerial surveillance; and social media intelligence, among other spy tech. CellHawk alone is powerful — but added to the area police’s already expansive arsenal, it tips local law enforcement toward becoming more like intelligence agencies than municipal cops.

Lengthy data retention policies and the power of these surveillance tools create a litany of frightening possibilities for overreach and abuse. While HCSO has acknowledged its use of some of these tools, it has not released any public reports on its use of CellHawk. Rachel Levinson-Waldman, deputy director of the Brennan Center’s liberty and national security program, who reviewed Hennepin County’s policy said, “The reference to use is concerning, since that could significantly expand the time for retention.”

Minnesota state law requires an individual whose electronic device was subject to a tracking warrant be notified within 90 days if that evidence did not end up in court. This “tracking warrant” law has been on the books since 2014 and yet, judging from press reports in recent years, it’s not clear any one in the state has ever received such a notice or if a tracking warrant has ever been unsealed by the courts. The law seems to have been thwarted in part by police avoiding warrants and obtaining instead court orders under the much lower “reasonable suspicion” standard. This, despite the fact that Minnesota law clearly states, under a subdivision titled “Tracking warrant required for location information,” that “a warrant granting access to location information must be issued only if the government entity shows that there is probable cause the person who possesses an electronic device or is using a unique identifier is committing, has committed, or is about to commit a crime.”

The ACLU of Minnesota’s policy director, Julia Decker, voiced concern over the lack of oversight for the use of CellHawk in the state, emphasizing the need for high standards of oversight for surveillance technology. Decker also expressed concern over the retention of CellHawk and similar data for five years by Hennepin, which could pose a threat to civil liberties.

Hawk Analytics has a broad client base throughout the United States, as revealed by a survey conducted using the Freedom of Information Act. The investigation found that numerous agencies across different states, including the FBI, have paid for CellHawk subscriptions in recent years. Though the Madison, Wisconsin police department appears to have thousands of potential CellHawk records from 2018, they demand a hefty fee of $700 to examine and provide these records. This highlights the need for regulation and oversight of powerful surveillance technology, especially in the context of police reform discussions.