A Beginner’s Guide to Digital Elevation Models (DEMs): Data Sources and More

A Comprehensive Guide to Digital Elevation Models (DEMs): Data Sources, Applications, and FAQs

This guide offers a comprehensive overview of Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), addressing frequently asked questions about this popular geospatial dataset. In addition, it provides examples of how DEMs are used in various applications, including topographic mapping, environmental analysis, and urban planning. The article also covers data sources for DEMs, including government agencies and commercial providers.

Understanding Digital Elevation Models (DEMs): Definition and Applications

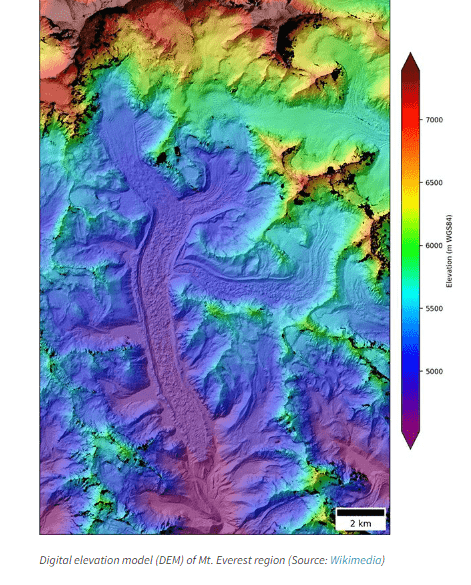

Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) are a type of digital geospatial data that represent the elevation of the Earth’s surface as a continuous dataset comprised of cells. Each cell contains location (X and Y) and elevation (Z) data, representing the elevation of a geographical feature. Unlike other maps, DEMs represent only the bare earth, without including data on vegetation, buildings or other above-ground features.

Topographic and bathymetric maps can be created using Digital Elevation Models to display overland and underwater terrain, respectively. Furthermore, using DEMs can enable the analysis of elevation data, such as calculating slope, aspect, and other terrain attributes, which are useful in applications such as environmental assessment and urban planning.

Common Digital Elevation Model (DEM) File Formats

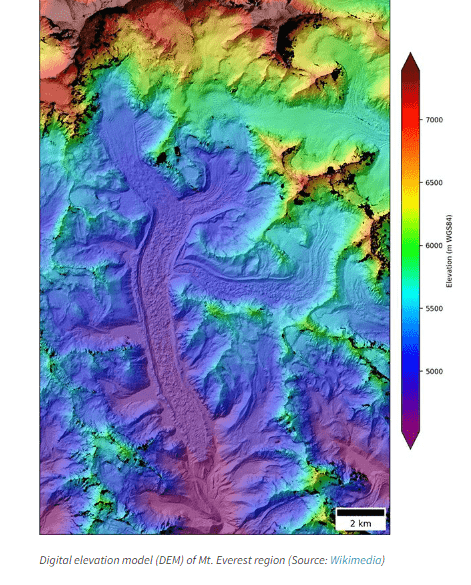

There are various file formats for Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), including IMG, Gridfloat (.flt), ArcGRID, and GeoTIFF. Among these, the GeoTIFF format is the most widely used, due to its compatibility with different computer systems and GIS software products. This interoperability makes it a popular choice for the geospatial community worldwide, allowing for seamless data transfer and analysis across diverse platforms.

What is a GeoTIFF?

Essentially, GeoTIFFs are raster files containing georeferencing information, like elevations, coordinate systems, ellipsoids, datums, and projections. A defined set of TIFF tags are used to convey information, all of which is embedded within the raster fi

In the 1990’s, the GeoTIFF format was developed by adding geographic metadata to the TIFF format as TIFFs are considered lossless and extensible. GeoTIFFs became a standardized format under the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC), who have specified requirements and encoding rules for using TIFFs to share georeferenced or geocoded imagery. The specifications can be found here.

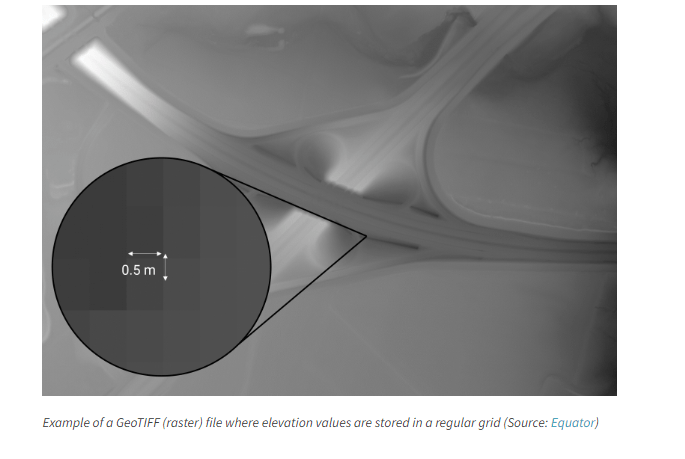

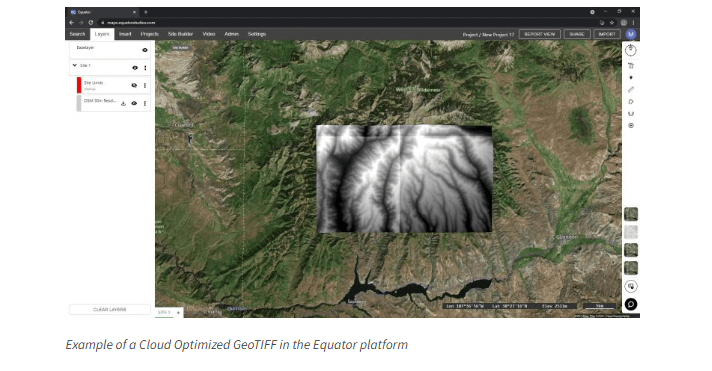

What is a Cloud Optimized GeoTIFF

Recently, a new imagery format designed for cloud-native geoprocessing in mind is being developed, called Cloud Optimized GeoTIFF (COG). COGs were created to solve the issue of large file sizes of raw data and the constant duplication of data when it’s being shared. Historically, data was duplicated many times because there was not an efficient method of storing or distributing geospatial data. The COG aims to solve this problem.

Essentially, COGs are GeoTIFFs hosted on an HTTP file server that leverages a better structure for processing (tiling, compressing) and storing the data. When you access COGs online, the system allows you to only access the section of the data that you’re interested in rather than downloading the whole file. Overall, this allows for fast streaming at full resolution and progressive rendering.

Essentially, COGs improve product processing time and storage, and support new cloud processing capabilities. In addition, legacy software can still read the file with no modifications because their underlying file format is a GeoTIFF, but there are several new software libraries and tools coming online that are aimed to support COGs. To learn more about this process, you can check out this lecture.

What is a raster file?

Raster data are cells (pixels) organized in a grid of regularly sized cells and represent some type of real-world phenomena. Although raster datasets are used in a GIS, you might already have experience with rasters if you have ever used a camera, since they are just digital pictures. When a raster is used to store elevation data, the size of the cell is typically determined by the spatial resolution of the satellite or LiDAR sensors used to collect the data.

Rasters can be classified into three different data types: discrete (thematic) data, continuous data, or pictures. Discrete (thematic) data is used to create thematic maps. These maps display phenomena which can be broken down into specific categories where each cell in the grid represents a distinct feature with clear boundaries. Discrete rasters usually use integers to represent different classifications of the dataset. For example, if we’re creating a thematic map to show the land cover of a particular area, then we would create a land classification where a cell with a value of 1 might represent agricultural land and a cell with a value of 2 might represent urban areas. Cells will then be coded by colour according to their values and two distinctive features will be visible.

Continuous rasters display phenomena which do not have abrupt or well-defined breaks between cell values but gradually vary in intensity from a specific source. For example, DEMs use mean sea level as a fixed point and each cell within the DEM represents a value either above or below sea level; the elevation value continuously changes across a landscape.

Pictures, like scanned maps or drawings, are also considered as raster data and can be used as basemaps over which other feature layers (like road networks) can be displayed.

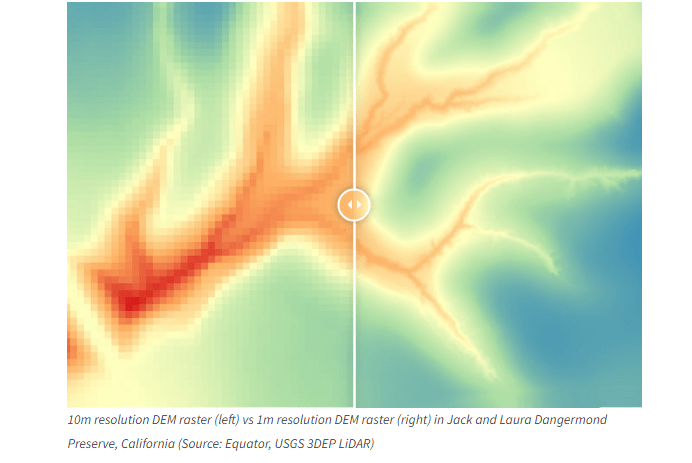

Raster files can potentially require a significant amount of storage space depending on the spatial resolution of the file. Spatial resolution, particularly for raster data collected through remote sensing or LiDAR, is typically determined by the sensor capabilities used to collect the data. In short, a higher resolution dataset, for example a DEM with a 1 meter spatial resolution, will require more storage space compared to a DEM with a spatial resolution of 20 meters. This is because a raster file with a 1 meter spatial resolution contains more pixels of smaller size compared to a raster file with a 20 meter spatial resolution; the more pixels (cells) there are within an image, the higher the resolution and feature spatial accuracy, and ultimately, the larger the file size. Depending on the extent and detail required to complete your project, it might be better and easier to use a raster file with a lower spatial resolution, especially if the area you’re studying is broad and does not require a highly detailed dataset to complete your analysis.

How are DEMs created?

There are several methods that can be used to generate digital elevation models:

Ground surveying can be used to create Digital Elevation Models, however, this method is extremely time consuming and laborious.

Stereogrammetry techniques, such as aerial photogrammetry, are also used to create DEMs. Aerial photogrammetry captures images of the ground using aircrafts or drones with cameras on board and requires the study area to be photographed at several different angles. Slight visual differences appear where these images overlap, which gives these images a sense of depth, and it’s through this stereo overlap that we can extract 3D information from photographs. It’s also possible to generate a Digital Elevation Model through Visual and Infrared (VIR) imagery. However, visible and infrared light waves are not capable of penetrating weather clouds and are not effective at night.

Radar interferometry is also used to measure elevation data and is capable of mapping the ground in bad weather and at night, unlike VIR imagery. This is because radar signals are capable of penetrating clouds and it’s an active system. This means that it illuminates the surface of the Earth with electromagnetic signals of a specific microwave length and then measures the reflected light. So, active systems can collect images of the Earth even when the sun isn’t present! Interferometry gathers elevation data through successive passes of the Earth either through spaceborne or airborne Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). In order to collect this data, a pulse of radar energy is emitted towards the surface of the Earth and then reflected back towards the sensor onboard a satellite or airplane. Two types of information are recorded after the waves are bounced back – amplitude and phase. For the purposes of generating elevation data, phase is the most important data. Phase records the distance from the satellite to the ground and back again, in units of radar wavelength. By comparing the phase value for each pixel in two radar images, and after computation and a series of geometric corrections are made, altitude values are determined and high quality digital elevation models can be generated. This method of collecting data can be accurate to within centimeters; an example of a spaceborne craft that used this technique is the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) which launched in 2000.

A multibeam echo sounder is used to collect bathymetric data. The echo sounder transmits pulses of sound into the water and the sound waves that are echoed back towards the echo sounder are recorded. The time it takes between the emission of the sound pulse and its return is used to reach an estimation of the depth of the water. This can either be accurate down to several centimeters or several meters depending on the sounder itself and the distance between the sounder and the geological feature. This device is typically mounted beneath or over the side of a research vessel but this data can also be collected using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). Check out Sea-Kit as an example of an autonomous research vessel! However, it’s also possible to use satellite remote-sensing techniques as well as LiDAR to collect this data.

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR or Laser Altimetry) is the final method on our list that can generate a Digital Elevation Model. A laser altimeter is typically installed on a plane or drone (but also on satellites; check out NASA’s ATLAS on the ICESat-2) and works by emitting a series of short laser lights in a sweeping motion, side-to-side. These lights travel to the surface of the Earth and are then reflected back to the laser altimeter. When the light is detected by the laser altimeter, a time counter, which began when the laser lights were first emitted, stops. In order to generate a laser (LAS) dataset, a simple series of mathematical equations are completed to determine the distance the light traveled to the ground. Check out this video to learn more about how this is calculated! The LAS dataset that’s generated then needs to be interpolated in order to produce a continuous raster dataset for elevation – then voilà! You’ve got yourself a DEM. You might also find that lidar data comes in a LAZ file format but this is just the compressed file version of an LAS dataset. The accuracy of this method can also be within centimeters of the location of real-world features.

Importance of DEMs and its Uses

Digital Elevation Models are a core spatial dataset required for many environmental, planning, and scientific applications. A few examples are highlighted below.

Environmental planning

Military applications

Emergency responses

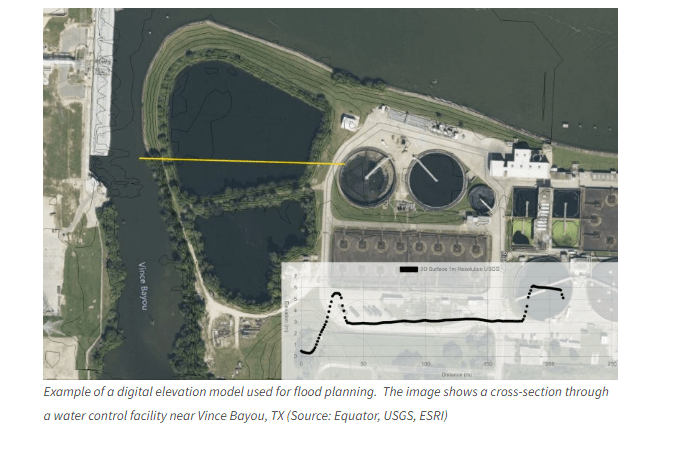

Hydrological functions: including drainage basin network assessments, understand drainage patterns, flood modelling and risk analysis

Slope and aspect models: created for thematic classification datasets and to generate hazard maps.

Transportation planning

Geological survey and analyses

Landscape archaeology: for example, using DEMs to search for microreliefs in the landscape, or monitoring changes in glacier ice-volume can also be determined by comparing DEM datasets generated at different times.

Topographic maps are also produced with DEMs.

Maritime transportation: Bathymetric data can be used to create nautical charts, monitor changes in coastline features, create conservation maps, and create important scientific models.

Case Studies / Highlighted Applications of Data

Exploration of Mars

As it turns out, we can use the same tools that we just learned about to map Mars. So, how about we suit up and head on over and see what’s happening?

n 1996, NASA launched the Mars Global Surveyor, a spaceborne craft. One of the many sensors onboard was the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA), which provided three-dimensional topographic data of the surface of Mars but had a spatial resolution of hundreds of meters.

In 2005, NASA launched the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter with the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) onboard, which can capture images at around 25 centimeters per pixel. Scientists then overlap images of Mars taken from different angles, and through stereogrammetry, can generate digital elevation models of particular regions of interest. These stereo images can then be used to create hazard maps of the area. This process is crucial in determining potential landing sites, especially for the Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in February 2021.

NASA’s Perseverance rover was able to use the hazard map in combination with its onboard sensors to scan the terrain during its descent in order to safely navigate and land in one of the safe landing zones that was designated on the hazard map. This allowed the team at NASA to land the rover in more geologically interesting, but more dangerous areas, than was previously possible. Furthermore, the Perseverance rover is also equipped with an enhanced auto-navigation system, called AutoNav, which has the ability to generate 3D maps of the terrain up to 30 meters away, identify hazards, and adjust its routes accordingly. This is done by taking pictures with stereo cameras which allows the rover to sense depth. As a direct result, the rover is able to travel more direct routes and reach sites of interest much more quickly than was previously possible!

Although space is fascinating, there are plenty of interesting projects involving the use of DEMs right here on Earth. Let’s splash back down and see what’s happening in our ocean before stepping back on dryland!

Sur Ridge Marine Exploration in California

We might initially think that the seafloor is flat and not as remotely captivating as the geological structures we find on land. However, just like on land, the seafloor is a complex and variable terrain but only around 20% of it has been mapped, let alone explored. For example, about 60 kilometers off the coast of Monterey Bay, California lies a large underwater geologic feature called Sur Ridge. It’s abundance of sea life had not been realized until 2013 when an ROV was first sent to explore the area.

Between 2015 and 2020, the Monterey Bay’s Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) has been carrying out survey expeditions to map out the region. They first began by using a 25 meter resolution ship-based multibeam sonar system before eventually using a Mapping Autonomous Underwater Vehicle to scan the seafloor at a 1 meter resolution.

MBARI designed a mapping toolsled with a hydraulic ram that’s capable of rotating the frame carrying all of the onboard sensors so that complex terrain, like vertical structures, can be accurately mapped. This mapping toolsled is flown at just 3 meters in altitude, and uses sonar, LiDAR, and stereo photography (illuminated by strobe lights), in order to map the seafloor. The sonar is capable of mapping at 5 centimeter resolution, lidar mapping is capable at 1 centimeter resolution, and photography is done at a millimeter scale because of this low altitude. The LiDAR is also capable of imaging the animals that are present, and the photographs taken are precise enough to identify species and show if the animals are alive or dead in order to quantify them. These images can then be geo-referenced to the bathymetric maps produced through the sonar and LiDAR data.

This comprehensive mapping allows researchers to study the geological, geochemical, and biological processes that alter the seafloor, as well as enable studies of habitats at the scales of the animals that live there. So, in a span of eight years, we have gone from knowing very little about this region, to being able to reconstruct this large underwater feature in great detail. A video of this reconstruction can be found here!

Finding and Viewing DEMs

Where can digital elevation models be downloaded?

There are typically three places where Digital Elevation Models can be downloaded: Government portals, University portals, or through pay-to-use sources.

Most governments provide freely available geospatial data, like DEMs, because it’s a part of maintaining an accessible, standardized, and organized geospatial infrastructure. Once the data is collected by an organization, it can be uploaded and can easily be shared and accessed by any number of users for their own purposes, which is also cost-effective. In Canada, you can use the Open Canada website, which is a searchable geospatial database with material made available by all provinces and territories. Although not a government website, the Canadian GIS site lists all open geospatial databases maintained by Canadian provinces and territories, and these lists also provide links to open geospatial data sites maintained by individual Canadian cities.

In the United States of America, there are three open geospatial portals that you can search for DEMs. There’s AppEEARS and EarthExplorer, where you can download the Aster Global Digital Elevation Model at 30 meters resolution and Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data at 30 meters resolution, respectively. Both portals require the use of an Earthdata login account, which can be made at no cost. Finally, LiDAR, as well as DEM data, can be accessed through 3DEP’s LidarExplorer, which provide LiDAR data at 1 meter resolution, and DEM data at either 10 meter or 30 meter resolution.

In Europe, you can obtain free DEM data at 25 meter resolution through the Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. However, you need to create an account, free of charge, in order to complete the download.

In Australia, you can access DEMs through Geoscience Australia, where DEMs of 5 meters and 30 meters can be downloaded. If New Zealand is your study area, then DEMs can be freely acquired through Land Information New Zealand.

Universities are also a great place to look for digital elevation models because they might provide links to open data portals available within the country that the university is in, portals created by other countries, or global geospatial portals. For example, the University of British Columbia (here or here), Simon Fraser University, Queen’s University, Ryerson University, and the University of Toronto are all great places to begin your search. However, geospatial data are obtained through academic licensing so any geospatial data that the university has can often only be accessed by affiliated students, faculty members, or staff, and sometimes a request form needs to be filled out in order to request licensed data that is not directly available through institutional websites.

Although ArcGIS Hub is a part of Esri, a pay-to-use GIS software company, you can search for digital elevation models on Hub and your search will return with entries from government organizations in GeoTIFF format, or sometimes ASCII format, that can, in some cases, be freely downloaded.

Paid sources can also be an option if you’re looking for higher quality data or for data that has yet to be made publicly available. L3Harris Geospatial offers many digital elevation datasets and has partnered with companies like Airbus and PlanetObserver to provide multi-resolution Digital Elevation Model coverage of the earth’s surface. They have offices worldwide.

Apollo Mapping also provides a platform to purchase DEMs in various resolutions. Earth Observing System sells high resolution images from a number of satellites (PLÉIADES 1 (1A, 1B), SPOT-5, SPOT 6, 7, KOMPSAT-3, KOMPSAT-3A, KOMPSAT-2, and SUPERVIEW-1). On board SPOT-5 are stereo instruments which allow for the collection of stereo images that can then be used for 3D terrain modeling. Although DEMs are not directly available, there are plenty of satellite sources available with a variety of sensors onboard from which you can generate your own geospatial data from!

Alternatively, there is Maxar Technologies, which provides access to Earth Observation and SAR data from the DigitalGlobe and MDA satellite constellations. If you’re in Canada and looking to hire a LiDAR survey company, LiDAR Services International, LSI is a Canadian based company that has been in the field since 2002 and has completed projects throughout Canada, the USA, and in Africa, Asia, Central, and South America.

Download 30 meter (1 arc second) digital elevation models

USGS Earth Explorer

https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/

Space Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data, temporal extent: 2000.

ASTER Digital Elevation Model (GDEM), temporal extent: 2000-2013.

ALOS PRISM Global Digital Surface Model, temporal extent: 2006-2011

Ontario GeoHub

Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (IFSAR)

Copernicus, temporal extent: 2011, spatial resolution: 25 meters.

Download 10 meter (⅓ arc second) digital elevation models

3DEP Lidar Explorer, only for the USA.

Download 1 meter digital elevation models

3DEP LidarExplorer, only for the USA.

LiDAR and DEMs available at 1 meter and 3 meters (1/9 arc-second)

Ontario GeoHub

Lidar

Methods for Opening Digital Elevation Models (DEMs)

Opening Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) using Free GIS Software

Several free GIS software programs are available for opening DEMs, among which QGIS stands out. QGIS is an open-source GIS software that provides its own toolset and integrates with other established open-source GIS programs such as SAGA and GRASS toolsets. Furthermore, it supports user-created plugins, making it suitable for a wide range of tasks, including terrain analysis.

QGIS has a smaller installation size compared to other GIS software and requires lower computational resources. Additionally, it provides rapid updates, plugins, and patches because of its extensive user-base. Extensive online documentation is also available for users to consult when using one or multiple functions.

Users can also install the QGIS Cloud plugin, which is a web-GIS platform for publishing maps, data, and services for public access. It is possible to opt for the paid version, QGIS Cloud Pro, to limit access to one’s maps. QGIS can be downloaded for Windows via two main options: the OSGeo4W Package suitable for advanced users that automates updates and avoids duplicating packages used by many other GIS programs, or the standalone installers. Other download options are also available for macOS, Linux, BSD, and mobile or tablet apps.

There are a plethora of options when it comes to GIS software, both for commercial and open-source options. One excellent open-source option is Whitebox GAT, which specializes in terrain analysis and offers advanced geospatial data analysis. Another is gVSIG, which offers 3D capabilities and OpenCAD Tools. SAGA GIS is another classic free GIS software that specializes in geoscientific analysis and can process LiDAR data while offering 3D visualization. GRASS GIS is an open-source option that offers digital terrain manipulation and is useful for generating digital elevation models.

For commercial options, ArcGIS by Esri is the main software company out there. Other options include CARTO, which is a pay-to-use web service that offers mapping and ASTER global digital elevation model data. IDRISI/TerrSet by Clark Labs specializes in remote sensing and GIS processing tools for environmental applications. Geomedia by Hexagon Geospatial offers GIS, remote sensing, photogrammetry, and data management software. AutoCAD Map 3D combines CAD and GIS capabilities for spatial data rendering in 3D. Autodesk’s Civil 3D software can also incorporate GIS data for surface modeling through point cloud data (LiDAR).