Why are mobile phones still prevalent in prisons?

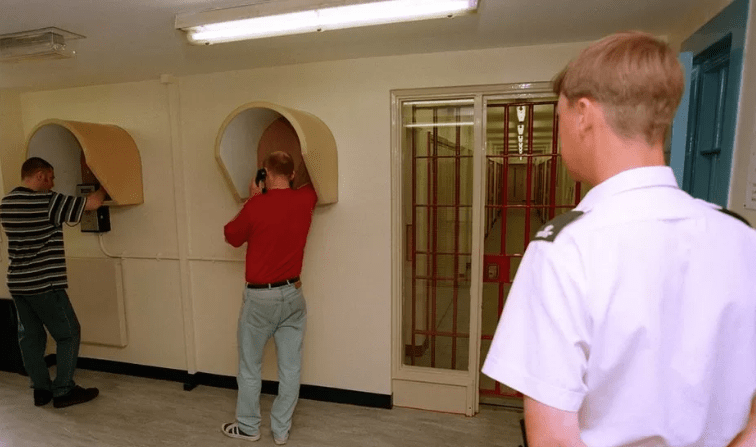

The issue of mobile phones in UK prisons is a serious problem that needs to be addressed. Despite thousands of phones being confiscated every year, many more are still being smuggled in undetected. These phones are a valuable resource for inmates, allowing them to continue their criminal activities even while behind bars.

The government’s National Offender Management Service has reported that many crimes have been planned and executed using mobile phones in prison. These crimes include murder, escapes, importing firearms, and drug trafficking. The problem is widespread and needs to be dealt with in an efficient and effective manner.

Security measures need to be improved to prevent mobile phones from being smuggled into prisons. Technology can be used to detect and track illegal phones, making it easier for prison staff to confiscate them. It is a serious concern that these phones are being used by inmates to commit serious crimes, and it is imperative that we take action to address the issue.

Cases such as machine-guns being smuggled into the UK by a prisoner, and inmates arranging murders and running drug rings from their cells, highlight the need for urgent action. It is time to use technology and expertise to improve prison security and prevent mobile phones from being used for criminal purposes. Only by doing so can we hope to create a safe and secure environment for both staff and inmates in our prisons.”

The mother of an inmate in HMP Northumberland claims “the place is full of mobile phones”.

“You’ve got people throwing mobile phones over the fences and then there are prisoners who have access to the grounds so they’re bringing them in,” she says.

Glyn Travis from the Prison Officers’ Association (POA) says the jail is far from unique.

“Drugs and mobile phones are freely thrown into prisons” with delivery by drone “completely undermining the external security that protects the public”, he says.

Sodexo, which runs HMP Northumberland, said “staff worked hard to stop illicit items getting into the prison using a range of technical and intelligence measures”.

But the fact that so many phones make their way into prisons despite security precautions goes some way to explaining how hard it is to find and remove them.

The obvious solution, says the POA, is to make them unusable.

Mobile phone jammers or grabbers – which block signals or divert them away from their intended destination – are readily available.

Cutting Communications: Four Effective Methods

Jamming/blocking: A signal is transmitted to prevent the handset receiving its base station signal. All phones and Sim cards within the jammer’s reach will be blocked, including those belonging to prison staff. The method is cheap and mostly effective. Interference caused outside the prison can, with care, be avoided, but this may add to the cost.

Grabbing: Phones are attracted to a fake network. It is selective – staff or nearby residents’ phones can be put on an unaffected “white list”. Success can be quantified – phones, and their owners, can be identified. Illicit phones can be monitored rather than blocked. It is more expensive than blanket jamming.

Operator disconnection: The 2015 Serious Crime Act introduced the power to force mobile phone operators to disconnect illicit phones. So far, the relevant regulations have not been enacted. Disconnected phones and Sim cards can be replaced and mobile operators may be unwilling to co-operate.

Stop and search: Visitors and staff can be searched for illicit phones. Cells and inmates can be searched to find those which are missed. Sniffer dogs can be trained to find mobile phones. Some phones will escape detection and new ones can be brought in to replace those confiscated

But NOMS says the expense is “disproportionate”, at up to £300m to fit and £800,000 a year to maintain.

However, technology installers, such as US company Cell Antenna’s Howard Melamed, have been downplaying the cost of the technology for years.

Steve Rogers, the managing director of electronic counter measures company Digital RF, says the UK’s wide variety of prisons – large, small, new-build, Victorian, open, high security – makes pricing “very difficult”.

“How do you value this, that’s the question, isn’t it?” Mr Rogers says.

“When you work out that value then you can say whether it’s affordable or not.”

The 2010 Crime and Security Act made possessing a mobile phone in jail punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine.

But inmates do not worry about punishment for crimes committed inside, Mr Travis says.

“I don’t know why they should fear the fact that, if they get prosecuted – and I use the word if they get prosecuted – by the CPS and the police, and then they go to the courts and they may get a 12-month concurrent sentence.”

Prisoners in HMP Northumberland know they are not allowed mobiles, but “lots of them” have them nonetheless, the inmate’s mother says.

Last year the government awarded a £60,000 contract to explore the use of mobile phones in prisons – how to stop them getting in, find those that do and disrupt those which cannot be located.

The previous year the Scottish Prison Service announced plans to pilot blocking technology at HMPs Shotts and Glenochil.

But NOMS specifically excluded such “prohibitively expensive solutions”, despite a change in the law in 2012 permitting their use in prisons.

Then, in 2015, the Serious Crime Act introduced the possibility of regulations giving the government – and ministers in Scotland – the power to force mobile phone operators to disconnect illicit phones and Sim cards.

Notably, the authorities would not need to find the phone to have it cut off.

The regulations are still to be enacted. A Prison Service spokesman said they would be “introduced in due course”.

But disconnected Sim cards and phones are soon replaced, Mr Rogers says.

And cutting people off is not in the commercial interests of organisations that make money “making sure people stay on air”.

“They only have to get one or two people wrong and they could be in a quite interesting legal situation,” he says.

The POA has been lobbying for signal blockers for years, raising it with MPs and each successive government.

“Every year they say ‘we can’t afford it, we’ll do a pilot scheme, we’ll do this’ and, whenever they try to do it, they say it causes too many problems – absolute rubbish,” Mr Travis says.

Mr. Rogers advocates for the use of grabbing technology in prisons. This technology allows prisons to track and disable mobile phones, and identify to whom they belong. He believes that blocking technology can sometimes leave small spots where a signal might break through, making it difficult to quantify its effectiveness.

According to Mr. Rogers, the success of this technology can only be measured by the number of phones that are thrown in bins by inmates who fear punishment for possessing an illicit item that no longer works.

The Prison Service acknowledges that prisons require urgent reform and that they need to explore new ways of finding and blocking mobile phones. Additionally, equipping prison officers with the right tools to tackle the issue is also crucial.

The article highlights the various security measures used in prisons, including detection equipment, routine searches, CCTV, sniffer dogs, and penalties. However, there was no clear stance on the use of blocking technology, and the spokesman refused to answer whether the 2012 legislation allowing for it had been implemented.

The Prison Officers Association (POA) believes that the use of blocking or grabbing technology would not only aid in controlling prisoners but also have a significant impact on society. The article raises a concerning point about how even those who have committed heinous crimes can organize crimes from within prison, raising concerns about the safety of the general public and our children.

The article lacked information on implemented pilot programs or any conclusions about the technology’s effectiveness and cost.